When I was about 8 years old my primary school teacher, frustrated by my reluctance to enter, pushed me into the pool at the town’s Baths. I thought I was going to drown but my fellow pupils came to the rescue. How could she have done this? What callousness! Or so the story goes. In truth I’m not sure the incident ever happened. However, I’ve told the tale so many times, often embellished, that I’ve come to believe it. Why the need for this dubious childhood anecdote? Certainly it has served to excuse my genuine fear of putting my head under water. Friends who have sought to teach me to swim can attest to my frenzied splashing in protest. Indeed it appears to explain my life-long struggle to stifle frightening dreams, within which I experience being suffocated, physically with a pillow, or psychologically by guilt, having betrayed my beliefs or people dear to me. I awake dramatically, fighting for my breath. By and large I deal with this, park the neurosis in its place. And then again, perhaps not.

For over the last four years, in particular, I have felt suffocated, drowning in an unrelenting deluge of information, opinion, analysis and gossip. I experience being in a state of alternative asphyxia. It is not that I am starved of the oxygen of ideas, rather I gorge, I binge compulsively on their 24/7 availability. Some sort of diet beckons.

This self-indulgent, breathless cry for relief from the day-to-day assault on my senses inflicted by the media of whatever ilk is very much personal. It is not to be taken in any way as an argument against the widest possible array of views being out there and accessible. I oppose censorship, the suppression of opinion, most of all when I disagree even vehemently with such speculation. I stand against authoritarianism, whether dressed in the cloak of the Left, Centre or Right. Obviously I have no time for the manufactured categories of mis and disinformation through which the powerful seek to silence criticism and opposition. Plainly the charge of misinformation is directed principally at those who question the dominant narrative. It is applied to those who desire to make public what the ruling class wishes to remain private. According to the ever suave Barack Obama, I’m severely mistaken. I’m sinking into the ‘raw sewage’ pumped into the public square by the alternative media. Thus, misled, he opines it’s no wonder I’ve lost faith in society’s politicians, institutions and media and in doing so I represent a disturbing threat – let’s not mince his words – to the future of humankind. Given this apocalyptic charge, it’s no surprise that the 2024 World Economic Forum in Davos is deeply bothered about my dissidence.

In his opening remarks to the conference of the great and good, Klaus Schwab, its founder and chair expressed his concern – “We must rebuild trust – trust in the future, trust in our capacity to overcome challenges and, most importantly, trust in each other.” In order to win back my undying support the elite will continue to encourage the creation of an armoury of so-called ‘independent’ disinformation agencies, funded by a mix of private and public sources. For example the European Union has “a network of anti-disinformation hubs that are part of the European Digital Media Observatory (EDMO), the independent platform for fact-checkers, academic researchers and other relevant stakeholders contributing to addressing disinformation in Europe”. Forgive the obvious but there is not the faintest scent of humility in these manoeuvrings, the slightest nod of recognition that their arrogant and authoritarian programme of propaganda and restriction might have something to do with our mistrust of their motives.

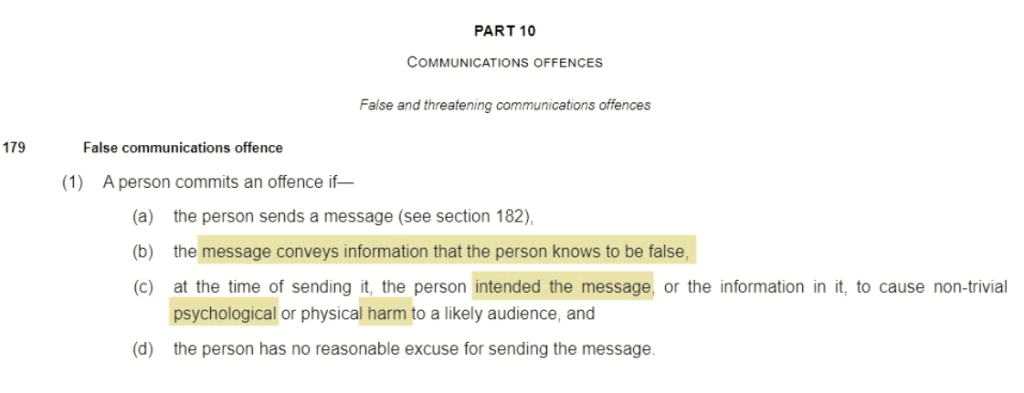

In the UK’s recently passed ‘Online Safety Bill’ you can see how the government intends to win back our trust. Section 179 section makes it illegal to publish false information with intent to cause harm…..

…..but Section 180 exempts all Mainstream Media outlets from this new law!

Of course I might not be seeing the wall for the bricks but this suggests strongly that the MSM are explicitly permitted to “knowingly publish false information with intent to cause non-trivial harm”. Yet you or I can be imprisoned for a year for committing a criminal act in drawing attention to their conscious deceit. A touch topsy-turvy!

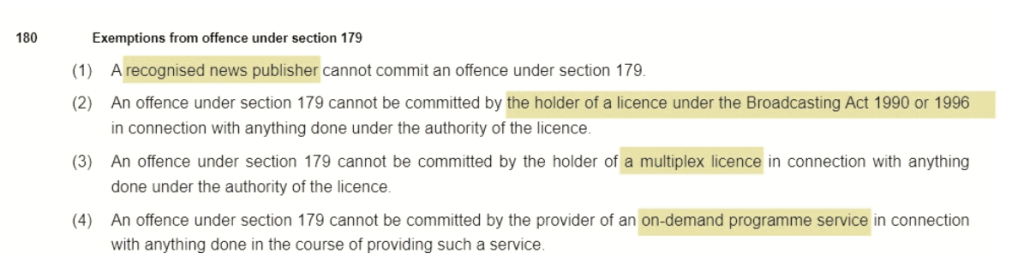

Hence, for my part, I will not be intimidated into accepting the powerful’s rule over what I think or believe. Perhaps you might think me simple but, on a day-to-day basis, I will proceed on the basis of receiving, reading and thinking about information. It will be whatever it is, a product of those who put it together, informed by their expertise or lack of it, their integrity, their prejudices, their beliefs and so on. It is my job as the aspiring, thoughtful citizen of Aristotle’s imagination to interpret and judge what I am told to the best of my faculties. Certainly such an ability, as far as it goes in my case, is born of a splicing of political activism with professional education and a measure of involvement in academia. At my most pretentious I fancied myself as one of Gramsci’s organic intellectuals.

In this context, summed up in the world of youth and community work [YCW] work, within which I laboured, as the desire to be a critically reflective practitioner, I didn’t expect to be so isolated as the COVID manufactured melodrama unfolded. I remain perplexed at the extent to which the professional class, including its YCW members, embraced and colluded uncritically with an unevidenced and unethical regime of societal restriction. An emergency was asserted but never proven. Fear provided its justification. Naively, I thought such authoritarianism would spark resistance. In retrospect, I failed to recognise how deeply behaviourism, its apparatus of preordained scripts, prescribed targets and imposed outcomes, was embedded in the professional psyche – not least in work with young people.This acceptance of a discourse of certainty about the correctness of our data-driven, objective models, the righteousness of our impact, the benificence of our worthy goals, spilled over into life as a whole. And, as far as I can see, practitioners remain in denial as to what they were up to. No more than fleeting research confirms that masking, social distancing [made up on the back of a cigarette packet], the closure of children’s and young people’s provision were harmful and unnecessary. I await the National Youth Agency even shyly allowing it was a touch over the top, even as it bemoans a deterioration in young people’s mental health. Evidently it was the virus ‘wot dun it’ not the conscious application by practitioners of draconian social policy. Perhaps, though I’m too harsh, even the much revered Noam Chomsky, ‘an intellectual superstar’, according to the Guardian, succumbed utterly to the smear that the unvaccinated were dangerous and irresponsible, arguing that they should be ‘isolated’.

Ironically and thankfully, Chomsky along with much of the Left recovered his balance as the seemingly endless tragedy of Gaza erupted, as genocide stared us in the face. Almost overnight we rediscovered our ‘instinctive mistrust of the state’, of careerist and opportunist politicians, of undemocratic, unelected bodies of experts. In particular, perhaps, having swallowed whole the COVID propaganda spewing from the mass media, we remembered belatedly our relentless and scathing critique of the bourgeois press, which goes back at least in academic and activist circles to 1974 and the creation of the Glasgow Media Group.

Enough is enough. I’ve peddled this perspective before without reaction, which is fair enough. Who on earth am I? My insignificance acknowledged, it does mean therefore that I must take a deep breath about my suffocating immersion in the currents of available opinion. It is extraordinary but I’m ‘sut on mi bum’ to use a Lancashire expression more than ever in my whole life. True, I still drag myself out more or less every day to indulge the narcotic of my lingering athletic obsession. I persuade myself I feel better for having done it. Yet, outside this hour or so of exertion, I’m sometimes spending up to eight hours hunched over the laptop in a pompous search for the Holy Grail containing ‘the Truth’! Inevitably it’s always just out of reach. I need a break from this self-inflicted imprisonment.

To cut my usual ramble short I’m determined to work out a fresh approach in my declining days. I need to get out more as the saying goes.

- I won’t abandon Chatting Critically but, in addition to my occasional originals, I want to use it more as a conduit to challenging thinkers and activists who you might not trip over. In doing so I’ve already culled the number of people I’ve been following because I can’t keep up. A future post will single out blogs and websites, which continue to stimulate me. You might well shake your head at my choices. On the ground I remain committed to our local Chatting Critically group.

- I shall spend more time on a project to record the history of the Lancashire Walking Club , of which I am a life member. It gives me pleasure, believe it or not, to do so.

- I am close to giving up on even being the In Defence of Youth Work [IDYW] archivist, the initiative of which I was once coordinator. Few seem interested. To all appearances its open-ended philosophy has been defeated – see the inanities of its supposed Facebook page, which ought to be closed out of respect to IDYW’s corpse.

- I’m going to ramble and cycle as I wish without feeling the need to rush back home.

- I’m going to spend more time singing and becoming musically literate.

- I’m going to spend more time musing for the sake of musing in our village kafeneion.

- I cannot promise but I ought to improve my Greek.

On reading this afresh it ends up looking like a belated set of New Year’s resolutions. Given my past track record in keeping to such sensible proposals as cutting down on the village wine, the omens are not promising. We will see.

Tony Taylor

To end positively, let me introduce you to the writings of W.D. James, who teaches philosophy in Kentucky, USA and his substack Philosopher’s Holler

He explains:

Egalitarian Anti-Modernist philosophical ruminations on our contemporary conundrums. In my native dialect, a ‘holler’ can refer to a hollow (empty space), a yell, or a work song.

I’m thinking my way through our current times and I tend to do that by digging into the ‘classics’ of Westen political philosophy to see what light they can shine on the contemporary moment.

My basic stance is characterized by:

- Anti-Modernism

- Anti-Globalism

- Deep respect for pre-modern wisdom traditions, including religious traditions

- Liberty

- Defense of the opportunity for a good life for everyone

- A critique of the modern state

- Grounding in nature/reality, intellectually, morally, and existentially

For my part, TT speaking, I would recommend you download and dip into the free pdf, Egalitarian Anti-Modernism

CONTENTS

Foreword by Paul Cudenec

Part 1: Was Jerusalem Builded Here?

Part 2: Jean-Jacques Against the Pathologies

of Civilization

Part 3: Rousseau and the Evils of Inequality

Part 4: Rousseau’s Revival

Part 5: William Morris and the Political

Economy of Beauty

Part 6: William Morris – Dreaming of Justice

and of Home

Part 7: What is Wrong With the World?

Part 8: Chesterton Against Servility

Part 9: Catastrophe

Part 10: Egalitarian Anti-Modernism and the

Contemporary Political Landscape

I enjoyed and was challenged by its content and argument, given that for a long time in my political life I believed in the inexorable relationship between progress and the continual development of the productive forces. I’m less confident nowadays.